Voting has now closed

Stay tuned as we reveal the official Word of the Year 2024 shortly…

Scroll down to find out more about this year’s shortlist and previous winners

Learn more about our shortlist

Revealing our shortlist

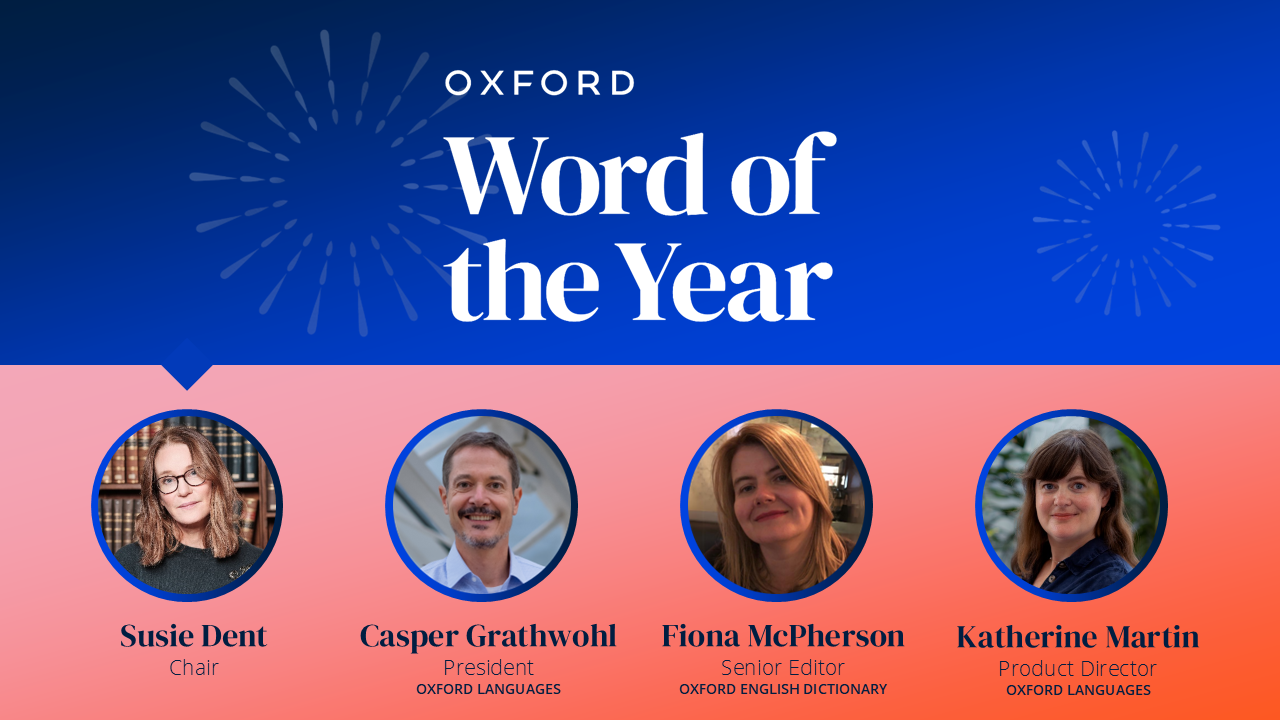

Catch up with with our announcement of this year’s shortlist, hosted by lexicographer Susie Dent with a panel of OUP experts.

Our approach

Every year, our lexicographers analyse the English language to summarize words and expressions that have reflected our world during the last 12 months.

We analyse data and trends to identify new and emerging words and examine the shifts in how more established words are being used. The team also consider suggestions from our colleagues and the public, and look back at the world’s most influential moments of the year to inform their shortlist—culminating in a word or expression of cultural significance.

In 2024, we’re delighted to be celebrating our 20th anniversary, as we reflect on the words that stood the test of time, as well as the ones that captured a moment.

Defining the past 20 years

Find out all about the history of Oxford Word of the Year with us.

We take a look at our past winners and shortlisted candidates, and explore some of the key themes, developments, and moods that they have captured over the years.

Recent winners

Read more about some of our winning words and how we chose them, with insights shared by our Oxford Languages team.

Related stories

brain rot

brain rot demure

demure dynamic pricing

dynamic pricing lore

lore romantasy

romantasy slop

slop