Oxford Word of the Year: defining the past 20 years

Since 2004, the Oxford Word of the Year has highlighted the language that has shaped our conversations and reflected the cultural shifts, patterns, and sentiments of a particular year.

Our expert lexicographers analyze data and trends to identify new and emerging words, and examine shifts in how more established words are being used, informing our choices for candidate words that reflect our evolving culture.

To mark the 20th anniversary of us celebrating the words that define a year, we take a look at our past winners and shortlisted candidates, and explore some of the key themes, developments, and moods that they have captured over the years.

Technology

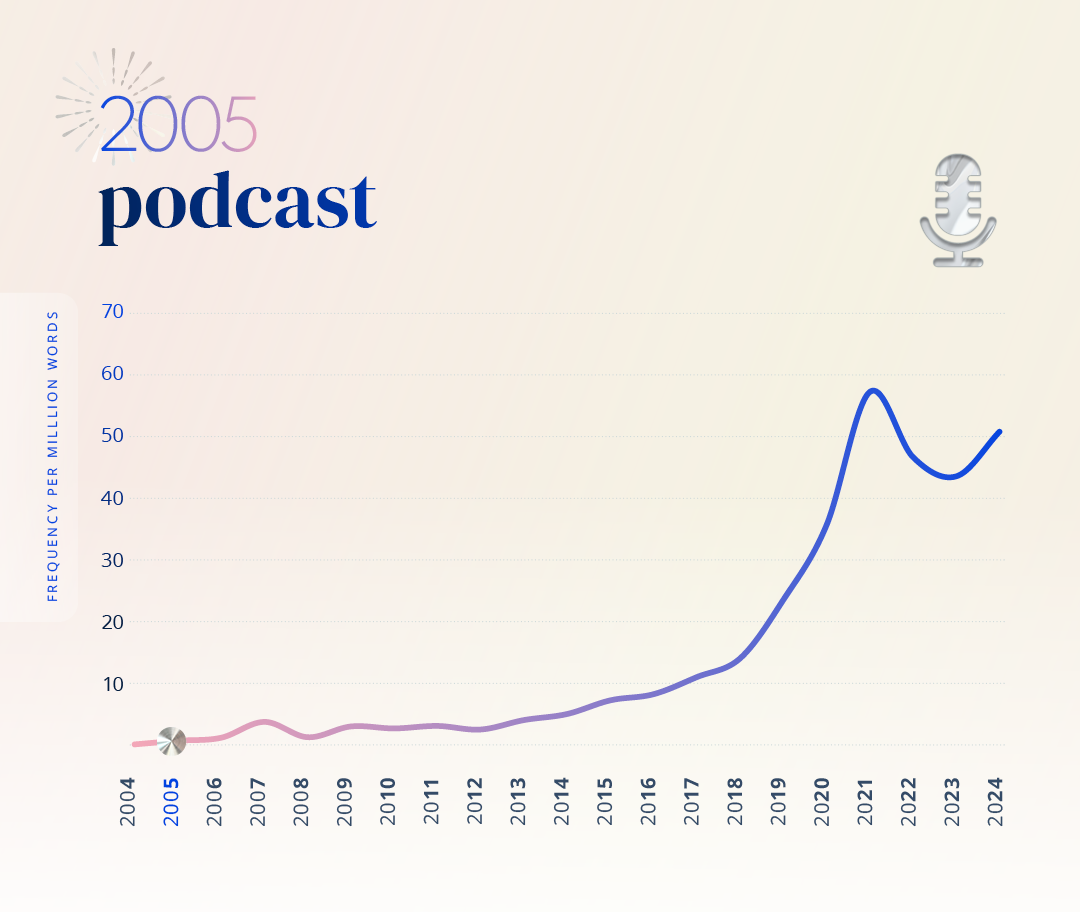

In 2005, our US winner was podcast (n.)—a compound of ‘iPod’ and ‘-cast’ (as in broadcast) which first appeared in 2004. By 2005, our experts noted that the word had grown in popularity and “caught up with the rest of the iPod phenomenon”. Fast-forward to the present day and iPods have all but disappeared, while podcasts are as popular as ever, with word usage increasing throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s.

Developments in phone technology have given us new, compelling ways to communicate with one another. In 2012, our shortlist included nomophobia (n.), or ‘anxiety about not having access to a mobile phone or mobile phone services’, resonating with those guarding against phone addiction. In 2015, our Word of the Year was actually an emoji, 😂, after research showed that it made up 20% of all emojis used in the UK and 17% in the US. The word emoji (n.) also tripled in usage in 2015 compared to the previous year, reflecting a wider uptake of this way of sharing thoughts and emotions.

In 2020, when life as we knew it was turned upside down because of the Covid-19 pandemic, we launched our Words of an Unprecedented Year report. It discussed the changes in language as we responded to working, teaching, studying, meeting, and even voting remotely (adv.)—which saw an increase of over 300% compared to the previous year, as recorded in the Oxford Monitor Corpus. Advances in communications technology helped us to adapt but we still needed to get used to using the platforms, with our experts also noticing an increase of 500% in the use of unmute (v.).

Whilst much of our lives went remote during the pandemic years, some technology companies turned their attentions to the possibility and sustainability of the metaverse (n.), where interactions take place in a virtual reality space. In 2022, the term moved from being used in specialist spaces into the public consciousness, with usage increasing fourfold as people discussed their vision of and for the metaverse, as well as questions around its ethics and feasibility.

Our more recent shortlists show that we are still adapting our language to be able to talk about new technologies, such as artificial intelligence. We shortlisted chatbot (n.) in 2016, whilst in 2023, we drew attention to a new meaning of prompt (n.) as ‘an instruction given to an artificial intelligence program, algorithm, etc., which determines or influences the content it generates’.

Social media and online culture

Language from social media platforms began to enter into our Word of the Year shortlists as early as 2008, when our US experts included tweet (n.), and our US Word of the Year in 2009 was unfriend (v.), meaning ‘to remove someone as a ‘friend’ on a social networking site such as Facebook’. In the years that followed, our shortlists also included words such as hashtag (n.), retweet (v.), and GIF (v.).

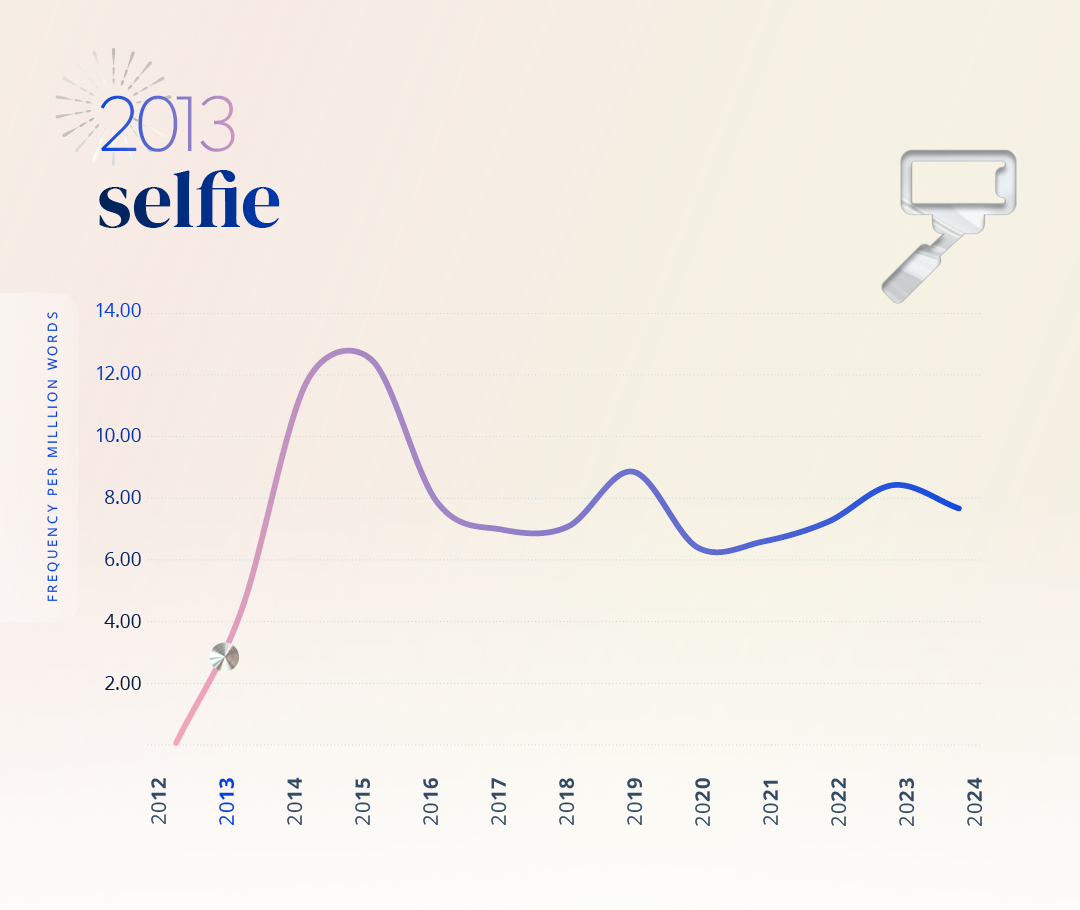

In 2013, usage of selfie (n.) grew by 17,000% on the previous year in our corpus, as it pivoted from a social media buzzword to a mainstream word for a self-portrait photograph.

Our more recent shortlists show that social media platforms are a place where words evolve within communities, and these words sometimes go on to be used more widely.

In 2022, we included a hashtag, #IStandWith, on our shortlist for the first time as the data we analyzed showed that it and its variants became significantly more frequent in March 2022 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The eventual 2022 winner, goblin mode (n.), went viral in February 2022 on social media, and seemed to capture the prevailing mood of individuals who rejected the idea of returning to ‘normal life’ after the pandemic.

Our 2023 winner, rizz (n.)—defined as ‘style, charm, or attractiveness; the ability to attract a romantic or sexual partner’—is associated with younger generations, and emerged from gaming and internet culture, with the American YouTuber and Twitch streamer Kai Cenat widely credited with popularizing the word in 2022, whilst an interview with the actor Tom Holland in 2023 brought the word into the wider social consciousness. Several words from our 2023 shortlist—including beige flag (n.), and Swiftie (n.)—also grew to prominence thanks to communities on online platforms such as Instagram and TikTok.

Interestingly, words that implicitly criticized some online interactions were also prominent in 2023, with our shortlist including de-influencing (n.)—‘the practice of discouraging people from buying particular products, or of encouraging people to reduce their consumption of material goods, esp. via social media’—and parasocial (adj.)—defined in our shortlist as ‘designating a relationship characterized by the one-sided, unreciprocated sense of intimacy felt by a viewer, fan, or follower for a well-known or prominent figure (typically a media celebrity), in which the follower or fan comes to feel (falsely) that they know the celebrity as a friend’.

Climate change

Language use around the climate and implications of climate change has become increasingly urgent over the past 20 years.

In 2006, our US experts named carbon-neutral (adj.) as their winner, and in 2007 carbon footprint (n.) was the UK winner, reflecting greater public discussion of people’s impact on the environment.

Words relating to sustainability have also proved popular in our early shortlists, with upcycling (n.) a shortlisted word for the US in 2007 and for the UK in 2010. Rewilding (n.) is ‘the process of restoring an area of land to its natural uncultivated state’ and was included in the 2008 shortlist.

In 2019, in response to heightened public awareness of climate science and the implications of irreversible climate change, our entire shortlist was themed around the topic, with climate emergency (n.) named as our Word of the Year. The shortlist included:

(n.) Actions taken by an individual, organization, or government to reduce or counteract the emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, in order to limit the effect of global warming on the earth’s climate.

(n.) The rejection of the proposition that climate change caused by human activity is occurring or that it constitutes a significant threat to human welfare and civilisation.

(n.) Destruction of the natural environment by deliberate or negligent human activity.

(n.) A reluctance to travel by air, or discomfort at doing so, because of the damaging emission of greenhouse gases and other pollutants by aircraft.

(n.) A target of completely negating the amount of greenhouse gases produced by human activity, to be achieved by reducing emissions and implementing methods of absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

(n.) A situation characterized by the threat of highly dangerous, irreversible changes to the global climate.

(n.) Extreme worry about current and future harm to the environment caused by human activity and climate change.

(n.) The fact or process of a species, family, or other group of animals or plants becoming extinct.

(n.) A term adopted in place of ‘global warming’ to convey the seriousness of changes in the climate caused by human activity and the urgent need to address it.

(adj.) (Of food or a diet) consisting largely of vegetables, grains, pulses, or other foods derived from plants, rather than animal products.

This topic has continued to remain at the forefront of people’s minds and conversations, with words such as bushfire (n.) and anthropause (n.) featuring in our Words of an Unprecedented Year report, and heat dome (n.) being shortlisted in 2023.

Politics and global events

The past 20 years have produced seismic political and economic changes that have impacted on people’s lives and the language we have used during these times.

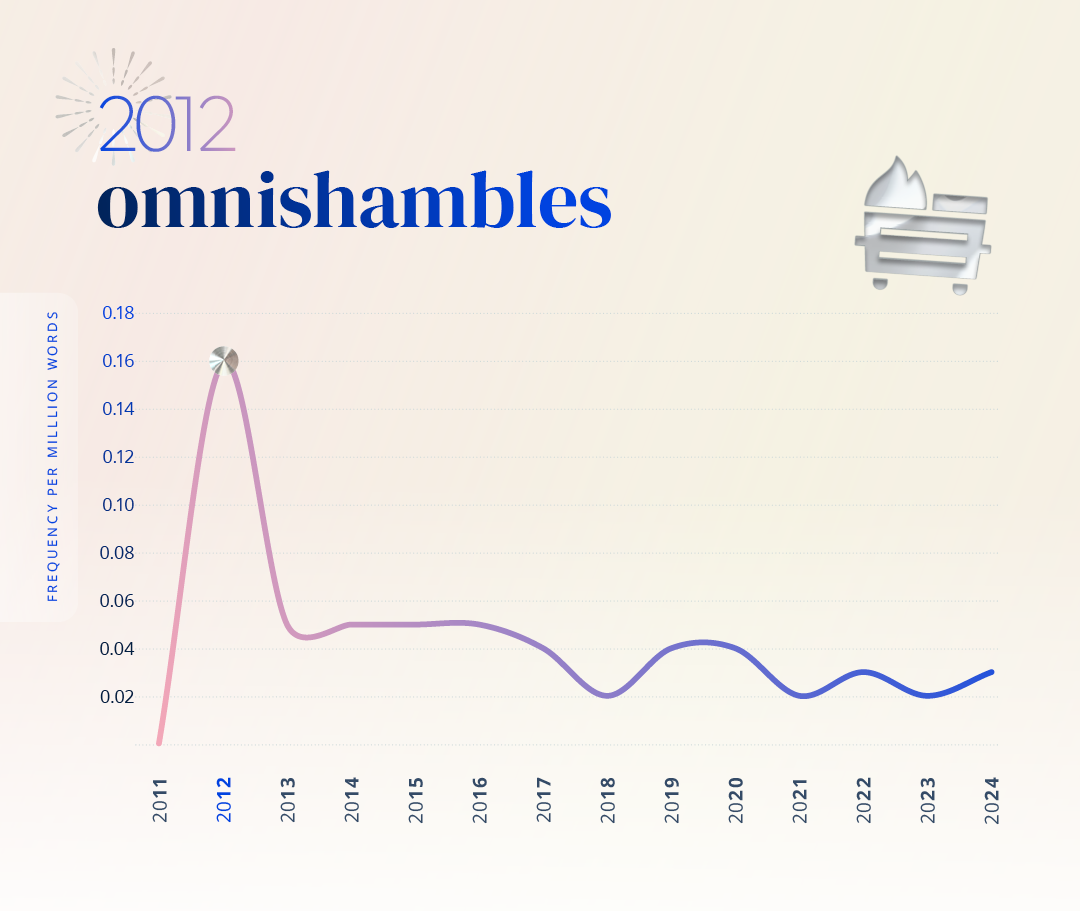

Financial crises and hardship have left their marks on years of our Word of the Year shortlists, with credit crunch (n.) being named UK Word of the Year in 2008 alongside a shortlist filled with words relating to economic difficulties. Great Recession (n.) was shortlisted in 2009 alongside staycation (n.) as people sought ways to take a break during difficult times. Eurogeddon (n.) was also acknowledged in our 2012 shortlist during Europe’s financial crisis.

Elections and referenda have also produced fresh words and concepts. Indyref (n.)—an abbreviation referring to the referendum on Scotland’s independence in 2014—made our shortlist the same year, whilst Brexit (n.) or Brexiteer (n.) were present in our shortlists for three consecutive years from 2014 to 2016. Our Word of the Year for 2016, post-truth (adj.), reflected how emotions and personal beliefs seemed to have a stronger influence on major votes, including the EU referendum in the UK and the presidential election in the US.

In our Words of an Unprecedented Year report, our experts tracked and explored seismic shifts in language as we responded to extraordinary events in 2020—not just relating to the pandemic through epidemiological and medical vocabulary, but also to social movements and the societal tensions that they uncovered. During the summer of 2020 and a surge of activism for the rights of Black people as well as other marginalized groups, terms such as allyship (n.), and systemic racism (n.) saw increased use with the latter rising by 1,623% between 2019 and 2020 in our corpus. Meanwhile, wokeness (n.)—the noun derivation of 2016 shortlist member woke (adj.)—became a tricky word to generalize about, as it was used to refer not just to a raising of social consciousness but also to social justice virtue-signalling. Cancel culture (n.) also experienced an uplift in use during this time.

And in 2021, the language of vaccines permeated all of our lives as medical breakthroughs and rollouts of vaccines against Covid-19 began in earnest, leading us to crown vax (n. and v.) as our Word of the Year. You can read more in our report.

The Oxford Word of the Year aims to capture moments of our collective social history through the language we use. Whether they have the staying power to remain a part of our language in later years, or simply define a moment in time, the many words we have explored and featured over the years are chosen by our experts for their potential to describe significant cultural trends, moods, and events.

You can read more about our 20th anniversary and past winners here—and be sure to check back very soon to hear more about Oxford Word of the Year 2024.